How Not to Disrupt Self-Storage

Self-storage startups like Clutter and MakeSpace may not be the most exciting “space” in tech, but they can tell us a lot about consumer-facing startups in general, and how the search for a simple narrative makes it impossible to understand how they really succeed or fail. In fact, the best way to frame them is through a sequence of simple-but-false narratives.

Narrative #1: Consumer Preference

The self-storage industry and its $38 billion in annual revenue are “ripe for disruption” with an “on demand” pickup-and-delivery model.

First of all, some of that is business customers, boat/RV parking, or other services where this on demand / “valet” model doesn’t apply.

But with individual customers, the storage companies have tried various pickup-and-delivery models in the past, and with some niche exceptions (like PODS) they’ve never really caught on. The incremental costs are hard to pass through, and directly handling the customer’s property is a different business from a liability/insurance perspective. And for most customers, the “pickup” service is solving a problem they don’t really have.

Many of the startup founders seemed to have a customer in mind that looks a lot like them: young urban professionals with tiny apartments (and often no car) who can free up space by rotating their seasonal wardrobes or ski equipment through a storage unit, like an extra closet.

This is a real customer demographic in a few big cities, but most storage demand is much less discretionary. Anyone in the business will tell you that it’s “need-driven,” by which they really mean event-driven, and they’ve got a morbid and alliterative list of these events: death, divorce, downsizing, dislocation, disaster… I’ve heard slightly different versions, but you get the idea.

Of course, many startup founders begin by targeting their own narrow demographic, and sometimes they can scale to a much broader market. But self-storage isn’t quite like taxis, vacation rentals or food delivery; the basic use cases are just different.

Narrative #2: Cost Structure

Even if consumers are indifferent between the two models, this one is more efficient without the expensive real estate and staffing.

For all that lifestyle and “Uber for X” startups talk about cutting out the middleman when they’re starting out, it’s uncommon for them to really achieve a lower overall cost structure, and they rarely try to compete just on price for very long. The reasons may vary, but in any case the storage startups seem to be following this pattern. “Passing on the savings” was part of the initial pitch, as in this 2014 interview with MakeSpace founder Sam Rosen:

Think of MakeSpace like a reverse Amazon. Rather than putting a little bookstore in a city center and filling it up with books where the price ultimately goes up every year because the store has to pay more rent, we instead run ourselves like a reverse Amazon. We move the facility outside of the city. We pass along that cost savings to our customers and we co-locate people’s bins with other people’s bins.

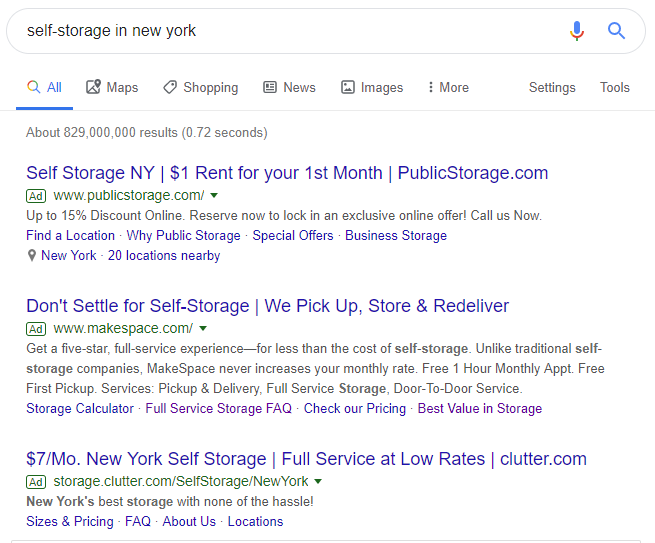

But today that seems like less of a selling point. All three of the following ads mention pricing, but only the first will give you a quote without going through a sales script to collect your contact information:

That’s not a criticism, just an observation. By all means, don’t lead with price if that’s not your business model. But if they were confident in their ability to undercut existing market pricing, it’s hard to believe they’d put customers through that high-attrition bottleneck.

Narrative #3: Platform

Even if this model isn’t more efficient, it creates a different kind of customer relationship, and you can layer on other features and services.

Now it’s getting interesting, because we’re finally getting to the question of what self-storage facilities are actually selling.

Why is self-storage such a great business? Because customers keep their units much longer than they expect to. Everything else flows from that: they’re less price sensitive at the outset then they otherwise would be, they overvalue near-term discounts like a first or second month free, the lower turnover helps you stay full and maintain pricing power, and so on.

But why do they keep their units longer than they intended?

It’s not just a question of laziness or “out of sight, out of mind.” Think about those D words again. The things people leave in storage are often emotionally fraught, and they don’t want to deal with them, especially if that will ultimately mean throwing most of them away. Even when customers visit their units regularly (which is more common than you might think) the prospect of clearing them out can be a daunting one.

In that sense a self-storage facility is selling stress aversion as much as space. And many of the “features” that the startups have tried to offer — like a photo catalog of your belongings, or ways to lend or rent them out — would have the exact opposite effect. In fact the entire “attention economy” mindset that dominates consumer-facing tech — using “convenience” or “connection” as a wedge for every service to insinuate itself into more of your life — is directly opposed to what many people want from a storage unit.

To their credit, the startups have clearly figured this out. Here’s another quote from that 2014 interview:

What if physical storage was categorized like our online storage? If I could flip through that storage facility the same way that I would look for a file in my computer or a song on Spotify… that was the genesis for this Dropbox for physical things or cloud storage for your physical belongings.

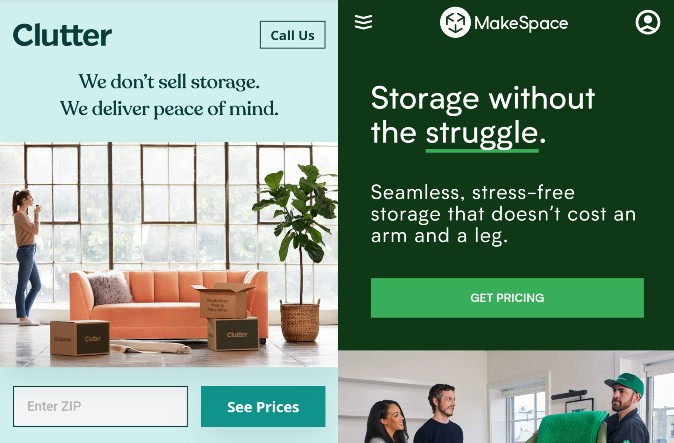

Contrast that with their slogans today, and how they’re appealing much more to the stress factor:

But there’s only so much they can do to deliver on that, because on some level the whole pickup and delivery model is in conflict with it. Instead of throwing everything in the trunk and driving to a storage locker, you need to sort it into their bins or boxes, measure oversized items, follow their packing rules, let them photograph and tag everything… you’re pulling forward a lot of that stressful sorting and decision-making that you were trying to put off.

And if you go through with it, that means you’ll probably be less averse to getting the stuff back and tossing it when you’re tired of paying the bills, and the delivery option makes that even easier. So even when the startups do capture a customer that would have gone to a standard storage facility, it’s not quite the same customer anymore and they may not have the same lifetime value.

Narrative #4: Separate Businesses

Maybe the startups aren’t “disrupting” anyone, but if they can tap into that new urban millennial customer base, they don’t need to.

Unfortunately it’s still not that simple. As you saw above, they’re still bidding on the same keywords. And as they raise more capital at valuations based on that larger need-based market, they still need to go after it even if they can’t do it profitably. So they’re expanding to more cities and growing their ad budgets, which drives up the cost of customer acquisition for everyone.

Is there any happy ending to that scenario? I’m not sure, but maybe we can learn something from other sectors. For example, think of all the “bed in a box” mattress startups: how much of their initial business was selling mattresses to Millennials who otherwise wouldn’t have bought one, because they were happy with their Ikea mattress and no one had tried to sell them something fancier?

In that sense, you could look at Casper as sort of the modern equivalent of the old Tempur-Pedic infomercials, with cultural signaling instead of NASA space foam.

What happened to Tempur-Pedic? I don’t know the whole story but they went public, opened stores, added wholesale channels, segmented their product lines and added more accessories, and eventually merged with Sealy. In general they started acting a little more like the older companies they had “disrupted” and I’m sure those companies tried to copy them in various ways, and the lines blurred. And despite a notable lack of profits, Casper is already well along on the same path. The outlook for convergence in the storage business feels a little hazier, but who knows?

Narrative #5: Complacency

The self-storage industry will “evolve” but it’s not vulnerable to rapid short-term “disruption” in the sense that we started out with.

You know what, I’m not sure about that either. For one thing, the startups may be accelerating the spiraling keyword costs, but they didn’t create that dynamic and it won’t go away if they do. You might say that the real tech “disruption” for this business has just been the shift to online customer acquisition, where the Facebook/Google duopoly has been slowly grinding away the margins for any business that falls into it. And maybe there’s some near-term tipping point — a recession, or some critical mass of overbuilding — that would flip that process into an even higher gear.

But here’s something else to think about: as the average stay gets longer, as the rent increases get larger and more frequent, and as the cost of new customer acquisition rises, even more of the value in the business is being concentrated in the long tail of existing customers, who have been there for years and just keep eating the rent hikes.

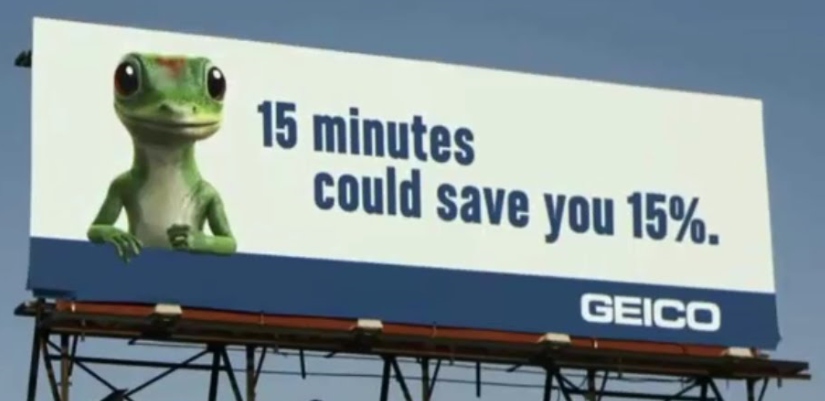

So if I were trying to “disrupt” that with a pickup and delivery model, I’d forget the search ads entirely and target existing customers rather than new ones. Think of those Geico ads:

What about a billboard that says “Did your storage facility raise the rent again? We’ll clear out your unit for you, cut your rent in half, hold your stuff as long as you want, and deliver it whenever you’re ready.”

This is admittedly a half-baked idea, and I can already think of some hurdles. Long-term existing storage tenants are a much smaller piece of the population than car insurance customers, and harder to target from a marketing perspective. You’d have to get each customer’s key or padlock code, sometimes an access card for the front gate, and maybe some facilities would make them show up in person anyway to officially cancel.

But it neatly answers many of the concerns we just walked through above. The pickup logistics would be much easier (flexible timing, non-residential locations), the value proposition is obvious, any aversion to a stranger handling their stuff is lowered if they’re not there to see it. And even as just a stunt to get your name out there for new customers, it might be more cost-effective than a lot of other options.

If you don’t like my suggestion, think about how you’d do it. One way or another, a business that’s dependent on fewer customers for more of its value is becoming more vulnerable.