How to Think about Loyalty Marketing

Nearly every consumer-facing company now has some kind of points or reward system. Some of them are creating real value and many are not, but they all use the same rhetoric and intermediate metrics. How can investors tell the difference?

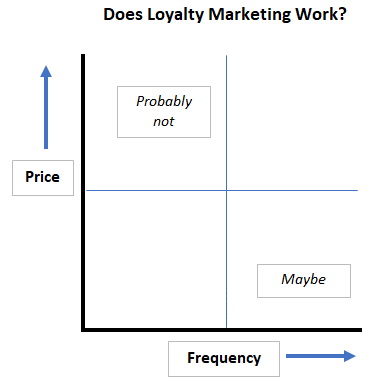

1) Frequency and Price

Let's start by visualizing what you already know:

In the extreme upper left, think of cars and heavy appliances. As you move down towards the center, you'll pass through electronics and fashion… and in the lower right, you'll get to fast food and coffee shops.

In the empty quadrants, it just doesn't come up as much. The lower left (low price, low frequency) would include things like sparkplugs, which are often mediated (e.g. by a mechanic) and often commoditized. The upper right includes rent, insurance, utilities… but in this case we're getting into credit and other overlapping dynamics, which we'll come back to shortly. (If anything, there's a trend towards penalizing/exploiting loyalty in these high price/high frequency categories, and erring on the side of higher churn.)

So you might be tempted to flatten this out into a linear spectrum, with price on one end and frequency on the other. But some of the most interesting investment questions arise in wholesale or platform models that span different parts of this graph. For example, groceries are on the middle right at the trip level, but on the lower right at the product level. If you already know something about the complex relationship between supermarkets and their CPG vendors, it can help to reframe it in terms of the tension between those two points on the chart.

2) Overlapping Strategies

If you've thought of exceptions to the pattern above, there's a good chance you're thinking of another mechanism that overlaps with loyalty marketing. Such as…

- Selling credit (e.g. store cards)

- Kickbacks for reimbursed business expenses

(e.g. airline miles, hotel points) - Subscription pricing models

- Membership retail

In this context, membership retail means a paid membership, like Costco or Prime, and that's what distinguishes it from the free "memberships" we're trying to evaluate. Another hint is that paid memberships are more common in multi-brand settings, rather than a direct consumer-to-brand relationship.

But for our purposes here, it's enough to note that these strategies work in different ways than the standard loyalty marketing toolkit, and we'd have to consider them separately before analyzing them together.

3) A Positive Example

Why does the relationship on our chart exist? The obvious answers are probably 80% of it. Behavioral conditioning works better with more frequent reinforcement, and "data science" works better with more first-party data. Consumers are naturally more likely to comparison shop with infrequent, big-ticket purchases, and sometimes we're also more variety-seeking.

To think about the other 20%, it helps to pick an example where a loyalty program has worked on you, and take a moment to introspect about why. You'll often find that it's not as straightforward as you'd expect.

For example, one of mine is Starbucks. Of all the new apps we had to download during the pandemic, this is one of the few that's still on my phone, and still earning Starbucks a higher share of my coffee consumption.

Is it my favorite coffee? No. Is it a better value than the places I prefer? Not really. Can I keep track of the loyalty points and offers? Absolutely not.

So is it more convenient? That's gotta be it, but it's still hard to be specific. I guess on some level I'm assuming a faster average prep time than the competition, and maybe not very accurately. And I guess I'm (even) less of a coffee connoisseur than I thought, if I'll walk past a place I like better to save 30 seconds of perceived time.

Well, am I really not benefiting from those other features? For example, sometimes when I order at the register, they'll remind me to use my accumulated points. And there are also times when I've pre-ordered and shown up to the wrong Starbucks, and they've made me the same drink anyway.

Those are perks of a product with very high gross margins — and also their "fortressing" real estate strategy, with more Starbucks in Manhattan than streetlights. Maybe you're aware of their problems with drive-thru lines in the suburbs, and other investor frustrations with their app and loyalty program. But that's why we're doing this from a customer POV, and why it's important to pick your own example rather than using mine.

And hopefully you're smarter than me about juggling points, and getting the most out of loyalty programs… but what you're really looking for is the points of tension that you were not aware of before this exercise, and that mild feeling of "huh, maybe they got me." This is what successful behavioral conditioning feels like, and it's a good sign of a loyalty program that's working.

4) Over-Optimization

On the other hand, you don't want to push things too far. For example, there's a certain kind of data nerd at SBUX (or their digital agencies) who just read my story and saw an opportunity. "Hang on, this guy says the point rewards are not shaping his behavior, so why are we reminding him to use them at the register? What if our new AI-powered blah blah blah can zero in on these customers who value prep time over rewards? Then we can nudge them higher in the order prep queue, with a point-of-sale prompt so no one mentions their points before they expire…"

I know they must be fun at parties, but some companies are taking way too much advice from these people. One problem with the above "strategy" is that you're giving employees another soulless little robot task and removing a positive-sum human interaction, which could weigh on morale and retention. You're also making it a little easier for me to drift back to the independent coffee shop next door, even if it takes some further nudge to make that happen. And then there's the incremental cost of maintaining and monitoring an even more complex system, right? Beyond a certain point, the diminishing returns on this kind of "optimization" are just not worth it.

Actually, I've been too hard on the data science team. The real story is usually just standard short-termism at the top. When c-level management wants to boost near-term reported metrics at the cost of long-term drawbacks that are more difficult to measure or attribute, that filters down through the whole organization.

So if you're a long-term investor who wants to avoid that kind of short-term management team, the countersignal that you're looking for is flexibility around their loyalty program, and more of a bias towards positive-sum thinking. For example, when a fashion brand has more overstock/clearance than they planned, are they saying "at least we can do something for our loyalty members by offering them these discounts first" or are they more worried about routing clearance away from high-value customers to protect their brand value?

Not that the second concern is invalid, and in this case we're talking about longer-term factors on both sides. But a healthy brand is always balancing them, rather than treating their loyalty program as a pure optimization exercise.

(One example of a brand that I get this positive vibe from is LULU, and it's not surprising that they're also a rare example of a DTC brand that has experimented with paid memberships.)

5) Bullshit Detection

When companies in the muddy center of that chart are using the digital loyalty playbook for the wrong reasons, there are certain other phrases they converge on. As with #3, it's best to pick your own pet peeves here, because you'll notice them more readily. But here's one of mine:

Our omnichannel/multi-channel customers spend 3x more than our single-channel customers…

Sometimes it's 2x or 4x. What on earth does this stat mean?

If it's not implying a causal relationship, it doesn't mean anything. But if it is implying causality, then it's off by an order of magnitude.

In other words, it makes sense that getting a store-only customer to try your website/app could drive higher spending, but a realistic goal would be closer to +10-30% than +100-300%. If this was really a multiplier effect, it would be the only marketing strategy in the world.

So how are they getting there? Maybe they're not adjusting for the number of transactions — i.e. every single-transaction customer is being treated as a "single-channel" customer by default. Or maybe they're also including untagged/cash transactions, and treating each of those as a separate customer.

Look, I hope it's not that stupid, because those approaches would be right on the edge of lying. I mean, suppose I told you that I analyzed the matchups in a week of MLB games, and found that pitchers who varied their first pitch to a given batter recorded 3x more strikeouts!! Then suppose you discovered that I wasn't just looking at starting pitchers, or adjusting for innings thrown, and my data set was padded with relievers who may have only faced each batter once. Would you trust any more of my data-driven insights?

But whatever these companies are doing to get that stat, it has to be pretty stupid. And of course, I'm not suggesting that public company CEOs actually believe every stupid talking point that someone gives them to read. But this is one that you would not read out if you actually took this stuff seriously, and that's why you'll almost never hear it from those higher-frequency consumable businesses in the lower right quadrant.

So when you hear it from CEOs in apparel and other lower-frequency retail, it's not a red flag in the same way as those signals of short-termism in the last section. But it's a pretty good sign that they see their loyalty data science as more of a sop to tech-obsessed analysts than anything that's really moving the needle… which is a good sign that you can ignore it too.