REITs are not Real Estate

"Every serious subject seems to undergo a kind of inductive metamorphosis, in which what has previously been assumed without discussion turns into the central problem to be discussed."

— Northrop Frye

"When you invent the ship, you also invent the shipwreck."

— Paul Virilio

In this note, I'll explain the current state of the US REIT sector in two simple charts. It's a little contentious, but it won't be boring. And for any institutional investor who has to think about REITs at all, I can promise to cut through a lot of fluff and save you a lot of time.

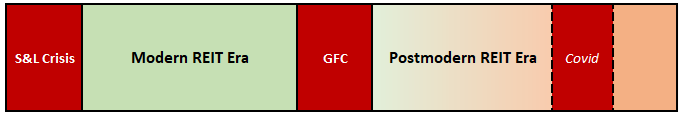

1. The "Modern REIT Era" is over

The REIT boom that began in the '90s was a powerful upward spiral. One company after another was backed into the public markets ("S-11 or Chapter 11") and then forced into better governance, better disclosure, and better capital allocation — leading to higher valuations, deeper research coverage, and constructive M&A.

For at least a decade now, this tape has been running in reverse.

On the way up, one slogan of the MRE was "REITs are real estate" — which I'll shorten to RARE from here on — and it may have sounded strange to other public investors. What else would they be?

But it was really a pitch to pension funds and other allocators for their direct real estate buckets, not just their public equity portfolios. The idea was that REITs would provide the same exposure and returns with greater transparency and liquidity, and a lower effective fee load.

Which they did, more or less. And in theory, that should have led to healthy NAV premiums, more IPOs and acquisitions, and continued AUM growth. But it didn't.

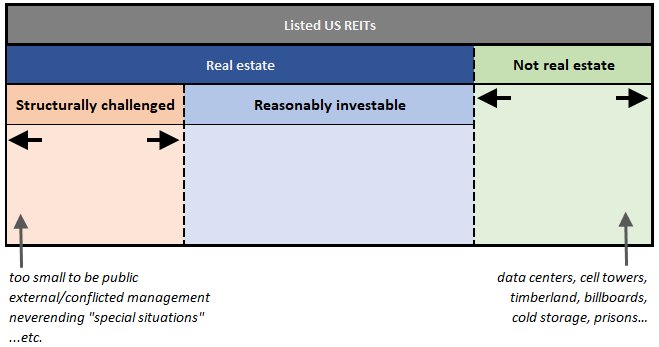

To see this more clearly, we have to look at the current universe in three parts:

This is not about what's in anyone's index or coverage, and I don’t mind if you want to use a marketing term like “specialty real estate” for the group on the right. There's no reason that a REIT team can't cover them. But not many people were calling this stuff "real estate" before they were lobbying for REIT status, and there isn't much overlap in the business drivers or analytic toolkit. It doesn't have much to do with commercial real estate as a meaningful asset class.

The companies on the left are not a great proxy for real estate value either — or at most, you could say they're a one-way ratchet, right? Falling asset values are invariably passed through to shareholders, but rising portfolio values tend to melt away into fees and comp. Even takeouts are less lucrative than they were in the MRE, and it often takes further value destruction to make them happen.

So we'll come back to this core group in the middle, but you can already see why no one else is showing you these two charts, and you can see the double meaning of my title. On the one hand, the REIT sector is being taken over by non-real estate "property types." On the other hand, that's partly because REITs have failed to serve as the liquid proxy for real estate that everyone wanted them to be.

Again, the first problem is not even really a problem. If real estate owners are using the public REIT structure less, it's hard to complain about other asset-heavy businesses taking advantage of it. It's just important to analyze them on their own terms, rather than trying to shoehorn them into a real estate framework.

The second problem is trickier, and it's upstream of everything else you hear about REITs that doesn't add up. For example, the media loves to use public REIT pricing to spin narratives about urban doom loops, walls of maturities, gating at non-traded REITs… but at best, this is a very blunt instrument. If deep post-Covid NAV discounts at office REITs were meant to tell us something quantifiable about the post-Covid office sector, what does it mean that they were already trading at deep discounts before Covid?

And for the most part, real estate investors seem to ignore these public market "signals," unless they're using them to trash each other's deals. "Why pay a 4% cap rate for Atlanta multifamily when the apartment REITs are trading at a 6," they'll ask, as they wait in line to pay a 5 cap for something those REITs wouldn't touch at a 7.

So another way to think about this is that CRE has been institutionalized without being fully securitized, or at least not in liquid public vehicles. Some of the more complex niche property types (like student housing) have now washed out of the stock market entirely, and some of the simplest ones (like medical office) seem to be on the same track. The only property type that did become dominated by public REITs was malls, and that turned out to be a severe case of adverse selection.

We're still talking about a massive asset class with very high transaction costs and fee loads, and further securitization is still a worthy project. But after a very strong start, the RARE approach is no longer getting it done.

2. So What Went Wrong?

I'll give you the top five answers that I've heard over the years. And I'll focus on the strongest and most pointed version of each, because this is where people will really start to waste your time; when you try to put these arguments nicely, you'll wind up saying nothing at all. So if I can't offend every target reader in this section, I'm not doing my job.

If we start by asking REIT-dedicated investors (and I used to be one) we'll hear a lot about governance, capital allocation, and "social issues." These are polite ways of saying that (a) too many underperforming REITs are becoming management/board enrichment vehicles, and sliding to the left on that second chart.

You can find versions of the underperformance-to-MEV pipeline all over the stock market, but it does seem to be a more slippery slope in REITland, even for management teams who begin with better intentions. It's the dual nature of REITs as a fund-like vehicle and an operating company, which offers too many degrees of freedom — and also the stable cash flows, which take a long time to grind away.

For example: when a REIT can't grow earnings and trades at deep NAV discounts for years on end, the RARE framework (or any finance textbook) would tell you to sell the company — or at least to shrink the portfolio and buy back stock. But you can also kick the can by churning and "upgrading" your portfolio to target the discount itself, or with other multi-year "strategies" that mix earnings and NAV approaches in vague and muddled ways. When they don't work, you can stroke your chin and blame whatever's in the news — the market, the Fed, the "consumer," the Knicks — and reset your stock comp, and start over.

Some of those management teams would turn this around, and say the real problem is that (b) REIT investors don't know what they want. “These funds claim to be long-term and fundamentally driven, but they also want earnings visibility and tight line-item guidance, and they drag us to ten conferences a year to ask how the quarter’s going. They want us to extract high returns from safe core properties, without enough leverage to bid on them, or enough overhead to retain talent. If we tried to play their NAV-arbitrage game on top of all that, they'd wind up with a REIT sector so textbook-perfect that it no longer exists."

Generalist investors are more likely to say that (c) the whole REIT sector is too cozy, and that's more politely than I've ever heard them put it. To the extent they're even listening to this debate above, it comes off as performative and fake. After all, aren't more of these c-level jobs and board seats now being filled by REIT vets from the buy side and sell side? Aren't these dead-in-the-water companies making REIT indexes easier for investors to beat, and aren't their boards being reelected? Doesn't this sound more like a lucrative little workfare program at the intersection of an overpriced real estate market and an indifferent stock market, for people who can't hack it in either one?

The responses from REITland can be just as harsh. They'll tell you that (d) most generalists are negative on REITs because they don't understand them, not because of valuations or governance. And you can't talk them out of their Fisher Price mental models of "real estate," because they don't really want to get it right. What they want is another way to bet on interest rates (which they don't always understand either), or a "hedge" to smuggle in beta on non-REIT long positions, or an overblown theme they can ride for a few quarters…

OK, it's fun to write these rants, but again, I'm also trying to inoculate you against the weaker and whiny versions of each one. Let's move on to the excuse that all these public market players can agree on: (e) we can’t beat the private market on fundraising, even with better risk-adjusted returns. The agency problems that drive capital into illiquid alternatives are simply too strong.

When you hear this from generalists, it's usually about (corporate) private equity, or late-stage VC, or the current private credit boom. This is Cliff Asness of AQR:

I’m a selective gadfly. I’m certainly not negative on the whole idea of private investing, [and] my criticism has been narrowly focused on PE’s lack of mark-to-market valuations… the illiquidity and nonmarking were once implicitly acknowledged, appropriately, as a bug, but are now clearly sold as a feature. The problem is logically you get paid extra expected return for accepting a bug (possibly explaining some of PE’s historical success), but you pay by giving up expected return for being granted a feature…

I think he's right, and I think real estate was the OG case of this problem. I only caught the end of the MRE, but it was certainly part of the discourse back then. And unlike the management/investor or specialist/generalist debates above, I won't give you a counterargument this time, because I genuinely haven't heard one that passes the laugh test. Most of my smartest friends in REPE would just say "yep, thanks for the money."

So in retrospect, maybe it was naive to expect REITs to earn a liquidity premium, in an asset class where illiquidity — or "volatility laundering," as Asness calls it — is the #1 selling point. In other words, it's not only that the stock market doesn't like real estate; it's also that real estate doesn't like the stock market.

3. Where does that leave us?

If you've followed me through this vale of tears, the REIT sector will start to look like a much more interesting place. And the final bullet to bite is actually easier for investors who are new to the space. It's simply noticing that the REITs and property types with the best long-term track records have often generated less of that value than you'd think from passive ownership… and more of it from development, third-party asset management, operations, scale, and other forms of platform value.

In fact, if you listen to these top-performing management teams, many of them will talk about platform value until they're blue in the face, and some of them sound almost as fed up with the RARE routine as their underperforming peers.

Of course, I'm not suggesting that you don't need accurate NAVs, or that you can ignore real estate value entirely. That's still a huge component of the returns. But it helps a lot just to flip the order of operations — and approach REITs as companies in the real estate business, rather than arbitrageable proxies for their portfolios.

Beyond that, what you need as a generalist is an extra round of triage and re-calibration, along the lines of that second chart. What you're looking for in the "investable" bucket is value-creating platforms that you can buy for free, because the real estate is out of favor — with any further real estate discount as a margin of safety, rather than your core investment thesis. And there are always some good liquid shorts here too, in long-term challenged real estate where positive short-term trends are being over-extrapolated.

But on average, these stocks tend to be a little cheaper than they look. And yes, that's partly because CRE is in between stocks and bonds, and it will screen expensive if you only compare it to other stocks. But it's also that the RARE approach tends to understate platform value, however explicitly it's incorporated.

Conversely, REITs in the "structurally challenged" bucket tend to be more expensive than they look, and the standard investor mistake is to get stuck in complex value traps that keep moving the goal posts, and grind sideways or down for years and years. The screen you need here is "return on brain damage"… and even for companies like this that I genuinely like, the phrase I keep coming back to in investor notes is "just take it off your screen." I get my share of stock calls wrong, but I'm not sure I've ever been wrong about that one.

There are occasional counterexamples where you'll time the exit just right, or one of these stocks will graduate into the investable bucket. And of course, some of them can be very tradable, without being fully investable. But for longer-term investors, it's hard to get paid for turning over rocks at the bottom of the REIT sector, or digging deep on underfollowed names and special situations. Even if you're used to the long odds in that kind of non-REIT screen, you'll find that they're even longer here, and the potential upside is more limited.

Finally, you'll also need some triage in who you're listening to — and it doesn't have to be me, which is one reason I'm not giving you a list of tickers in each bucket. In fact, it helps to have your own rough definitions of "real estate" and "structurally challenged," just as a place to start.

(e.g. my criteria for treating a property type as "real estate" include the number of viable uses for a typical asset, and the number of potential tenants/operators for the current use… my threshold for "too small to be public" has drifted up to $1-2B of portfolio value, and $10-15M of ADV…)

If you found certain parts of that "what went wrong" section more convincing, or you had other thoughts about this post-GFC malaise in the first chart, keep those in mind too. Then you can bounce some of these views off the next person who pitches you a REIT stock, and you'll find out pretty quickly how serious they are. Not that they'll draw these lines in the same place that you or I did, and maybe they can talk you into moving them. What you're trying to avoid is someone who doesn't want to draw the lines at all, because they're just promoting a stock.

This is a long note already, and I promised it wouldn't be boring. So I won't get into a more formal account of how the RARE model became a victim of its own success, or the normative question of how the REIT sector could turn things around from the inside. But I've already covered some of that in prior public notes, and you can sign up for the email list (below) to see more. Finally, I am always grateful for feedback and disagreement: peter@plraresearch.com