The Online Retail Swamp

Nordstrom is the latest prominent retailer to adopt a "marketplace" model, accepting online listings from third-party sellers. Of course, Amazon is the best-known example of this approach, but will it work for everyone else?

I've been skeptical. From one of my recent investor notes:

If you have a well-known nameplate with a critical mass of e-commerce traffic, you can always wave in more third-party sales. But on some level, you’re selling your customers back into this online algorithmic sludge that they presumably came to your site to avoid, and you should expect that any bad experiences with third-party sellers will rub off on your own brand value and customer loyalty.

And in the long run, this algorithmic sludge of online shopping will tend to push sales into the largest and most efficient logistics networks (e.g. at AMZN or WMT) and commoditize the pure drop shipping models…

Given the growing importance of these investment questions, it's surprising how little they're even being discussed, and how shallow those discussions have been. As e-commerce has become more of an algorithmic black box, management commentary has become increasingly elliptical, and even more of a game of telephone — repeating talking points from their marketing team that have passed through a growing chain of digital agencies, data scientists, and consultants, without anyone knowing quite what they mean.

1. A Brand’s Eye View

An example of that elliptical rhetoric, from the recent Lands’ End earnings call:

Q: Is there potential to add other marketplaces? [And] you've previously talked about how you can now shift product between the different marketplaces; what are the opportunities there in terms of margin?

A: We're in process of adding a couple of elevated partners that we’re hoping to talk about in the next few months. At the same time, it's about continuing to work with the partners we've got. We particularly look at Macy's and Target, and opportunities to grow our business there…

And I think it's horses for courses… we want to get optimized on the assortment for each of those. There's a slightly different price point, there's a slightly different customer relationship, and there's a different customer journey that happens on each of those marketplaces.

So we tend to look at them in isolation. And it's not just price point related, it's product-related, and that's something that we continue to fine-tune. We have some fairly sophisticated tools we're able to apply against that.

Apply them against what, exactly? Is this an answer to the margin question, or is it more about growing sales? And if you're trying to maximize sales or margin across all of these marketplaces, what does it even mean to look at them "in isolation"?

I'm picking LE because their history makes them a relatively clean case study. After a long stretch under Sears ownership, they had almost no other third-party distribution when they spun out in 2014 — and since then, they've tried almost everything, including a number of their own brick & mortar stores. So we have plenty of commentary on what they're looking for from each new partner and channel, without legacy relationships clouding the picture.

For example, on warehouse clubs:

They get behind a few items and they get behind them really heavily… [and] the customer you reach in the club channels is very much a customer we're interested in getting. It's very much our traditional Resolver, but we see the Evolver customer, who tends to skew a bit younger, as well. And that has us reaching an older Millennial and Gen X customer, who tends [to] be upwardly mobile. So by having a narrow but deep assortment that continually changes, [we] think we can reach new customers and really drive the business in a way that accelerates all of our channels.

Without getting further into those psychographic targets — which have varied somewhat, across successive LE management teams — you can see another reason that a former catalog business makes a good case study. They have a Boomer customer base that's loyal but not growing, and still buying almost exclusively via direct online/phone orders. So it's relatively easy to distinguish them from these younger customer cohorts they're trying to reach…

2. A Customer’s Perspective

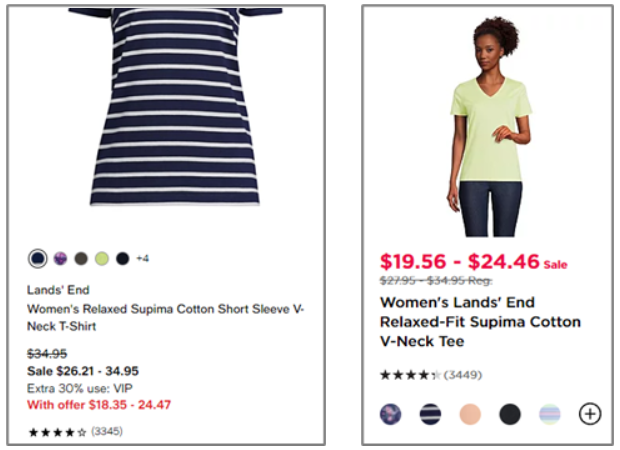

Most readers will know exactly what I mean by the “algorithmic sludge” of online shopping, but it’s worth a quick example. After that LE earnings call, I searched for “Lands’ End” on Macy’s and Kohl’s, and picked the first featured result — which happened to be this same t-shirt, on both sites:

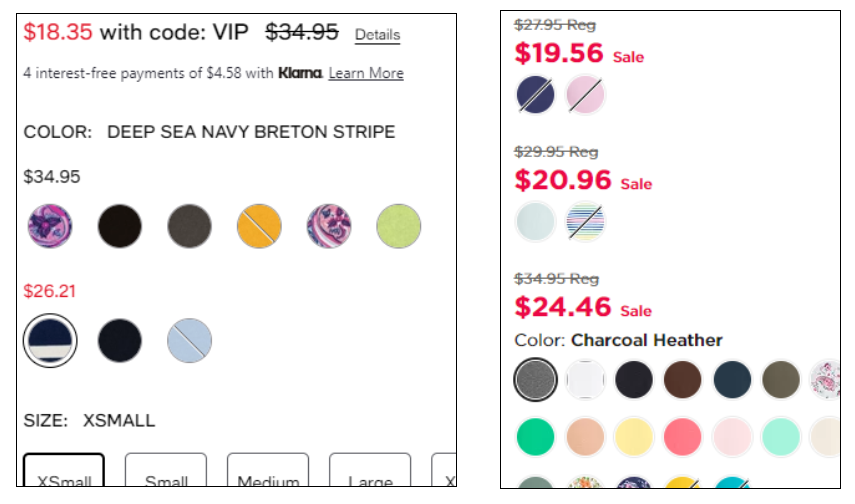

That's Macy's on the left, and Kohl's on the right. It's a 33% range in sale pricing ($18.35 > 24.46) and interestingly, Kohl’s is also showing a 25% range in base pricing (27.95 > 34.95).

You'd expect that most of this variation will be according to the popularity of each color/pattern, rather than variance between the two sites on exactly the same item. But they’re not making it easy to compare:

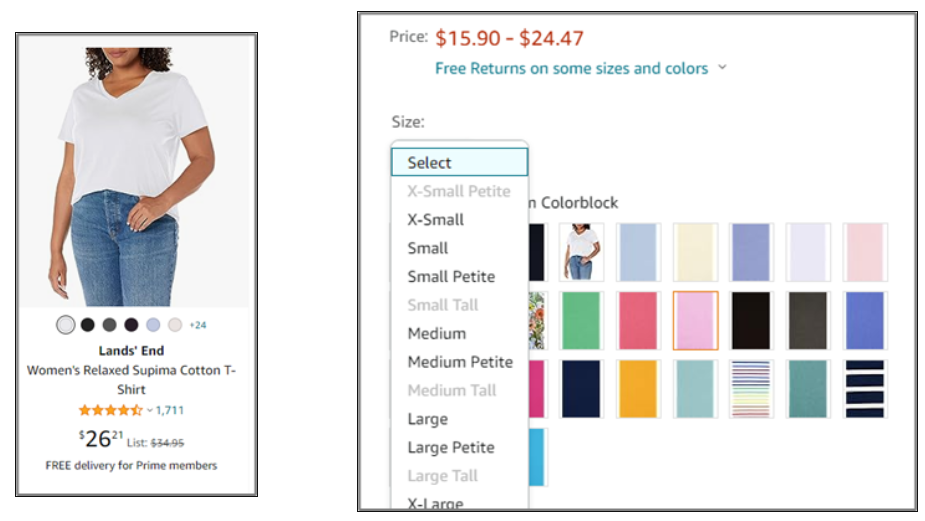

Amazon is a whole other level of complexity. They don’t show an overall range at all, the stock is spottier, and the pricing within each color also varies by size. Not only the pricing, but the terms for shipping and returns…

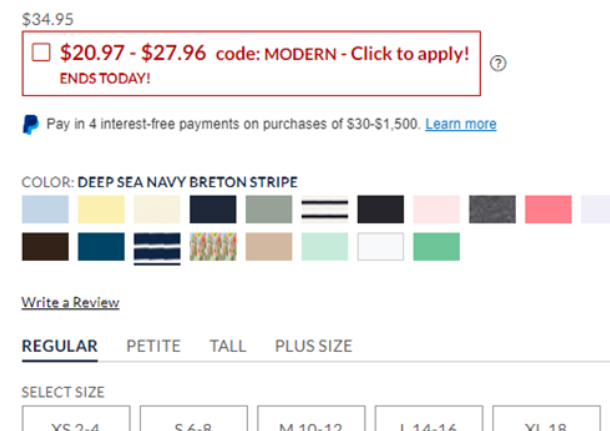

LandsEnd.com is the only place you’ll find the whole range of sizes and styles in a single listing, with a single list price. But even here, they’re making you click on each color to see the sale price:

Again, you've seen these trends for everything you buy online, right? Constant A/B "optimization" of the order path, often with Amazon a year or two ahead of the pack. It's one small step at a time, but the overall trend is to make comparison shopping more of a hassle — more clicks, less information on the same page, more confusing options, more complex discounting and loyalty schemes.

What's going on in this particular case? From the business side, I could tell you that LE's “marketplace” presence at Kohl’s and Amazon (but not Macy's) seems to be stacked on top of an existing wholesale relationship, which includes slightly different “exclusive” colors at slightly lower initial price points. I would note that Amazon’s marketplace has more small third-party sellers, who may or may not be using Amazon for fulfillment, and who may be sourcing their Lands' End stock in a number of different ways.

If you really had some time to kill, I could tell you about the vastly different warehouse and store footprints across these four companies, and what that means for inventory placement and shipping times. And if you know someone who works in apparel merchandising or logistics, you can buy them a drink and they’ll tell you a lot more than I can.

Which you should, because it’s interesting stuff. But none of that is helping with your immediate problem as a customer, right? You’re just trying to buy a freaking t‑shirt, without paying more than you have to. Like many other brands, LE is now lining up a gauntlet of irritating slot machines between you and that simple goal. As you just heard above, they can't even fully explain these "sophisticated tools" to their shareholders, but they're eager to tell them about the next few “elevated” marketplaces they’ve got lined up. Isn't technology exciting?

Well, let’s just focus on that Navy stripe in the first picture. It looks like $24.46 at Kohl’s and Lands’ End, $26.21 at Macy’s, and… $32.96 at Amazon??

LandsEnd.com it is. But now you’re paying $9 for shipping ($8.95 at Kohl’s) unless you meet a $100 free shipping threshold ($50 at Kohl’s), in which case you still may not get it for a week. And what about that 5% back in Kohl’s cash?

Also, that Amazon pricing was all over the map. Just clicking on a few other colors, I saw offers as low as $15.18. So even if you start at Lands' End or Kohl's next time, won’t you be tempted to click over to Amazon before checking out, especially if you're a Prime member? After all, they may have the same item with free one- or two-day shipping, and a much better all-in price.

Needless to say, this is not the kind of “customer journey” they had in mind on that LE call. But the point is that every online order path converges to this scenario. You’ve picked a product, brand and spec, and you’re ready to buy… but you’ve been trained by all these algorithms that you're almost certainly paying a little more than you have to, and possibly a lot more. And in contrast to in-person shopping, it only takes a few moments online to check the most obvious alternatives.

3. Intermediaries

One of my recent Walmart orders arrived in a Home Depot box, from a Home Depot warehouse. I’ve had a few similar funny experiences with drop shippers on Amazon or eBay, and maybe you have too. In this case, it looks like they scanned for products offered by Home Depot with free shipping, and marked them up as a third-party Walmart seller.

With a small item like this one, where the markup was only a dollar, you might wonder if this arbitrage is worth anyone’s time. But of course, there’s automation on this side of things too, and it’s a volume game. So this is one of the simplest possible examples, but there are many other mechanisms keeping the ecosystem of this online swamp in balance — up to and including private brand knockoffs, and outright counterfeiting. Which means that even for customers who have given up on doing any comparison shopping, there's still a rough limit to the amount of price discrimination that any brand can realize just by tweaking their offering across different sites.

My order was not exactly the ideal transaction for HD or WMT, but it’s a lot better than nothing. Home Depot gets the direct sale, and Walmart gets a commission. Both are getting valuable data. And it’s certainly not an accident that those benefits went to two 800-pound gorillas, right?

After all, this third-party arbitrageur could be listing the same product on a dozen sites, and sourcing it from a dozen others. But I'm more likely to buy it at a site like Walmart or Amazon, where I'm already shopping across other categories. And I'm more likely to buy it from a seller who can quote a fast shipping time — even if I don't know who they are.

Which reinforces my point at the beginning about the long-term advantage of logistics. Home Depot doesn't even need their own "marketplace" platform to benefit from others implementing them. They just need scale and speed.

Which don't come cheap — and when other legacy companies try to play this game in a more asset-light way, there's always an element of disintermediating themselves. In other words, they may present "marketplace" sales to their shareholders as entirely incremental, but we know that's not quite the case. If a Macy’s customer searches for a t-shirt and buys a marketplace listing, that's a shirt they didn't buy directly from Macy's — which has effectively traded a larger wholesale margin for a smaller commission. And for Lands' End, think about all those direct customers who are also Prime members, and are now seeing the brand at Amazon…

4. Equilibria

You can imagine a world in which all consumers have extremely high brand loyalty, and this complex game favors an established brand like Lands' End. They can sweep through the "marketplaces," collect their target customers, consolidate them back into direct channels, and wind down all that third-party distribution.

It's a little trickier, but you can also imagine a scenario that favors Macy's or Nordstrom. It would be something like high brand premia and low brand loyalty, with rapid creative destruction, and lots of differentiated new brands popping up. Too much turnover to justify the inventory risk in a traditional wholesale model. Too fast for Amazon (or H&M, Shein, et al.) to commoditize these brands and grind away their margins.

These are not the worlds we live in…

…and that doesn't necessarily mean that Lands' End or Macy's are pursuing the wrong strategy. After all, Macy's can't do much on their own about fading mall traffic, and Lands' End can't keep their direct customers away from Amazon. Even if they recognize this algorithmic swamp as a slow melting pot for brand value, it could be even more dangerous to sit it out. You might say they're just playing the hand they've been dealt.

But for investors, there's a huge difference between that kind of fighting retreat — in which the fading core business is arguably being cannibalized a bit faster, in order to maximize the salvage value — and the more common approach of treating every new digital "strategy" as purely incremental.

And even from a management perspective, there will always be some point at which the optimal strategy changes — some melting point where it's better to take a short-term hit to stand out from the sludge, rather than chasing the diminishing returns of even more "optimization." Which doesn't have to be a rotation back to physical retail; it could just mean taking on more inventory risk, taking more chances with design…

In any case, it would mean tuning out the "data science" and lean inventory dogma for a while, and recognizing the common-sense limits of algorithmic optimization for a business facing secular challenges. It may help to slow the decline and buy time, but it's not a way to turn things around. At some point, you have to take real chances again.