The Future (and Past) of Movie Theaters

The emerging investment pitch for a movie theater “comeback” is basically another year or two of reversion to the pre-pandemic pitch. Unfortunately, that narrative was mostly wrong. But it’s wrong in interesting ways that may tell us something about what could happen instead, or about the risks in other leisure and recreation businesses that look stronger today.

1. The Wrong Story

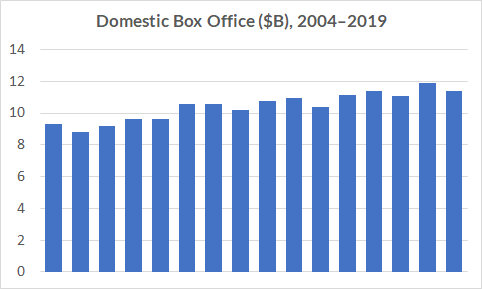

You may have seen a version of that pre-Covid investor pitch for theaters. It started with a chart like this:

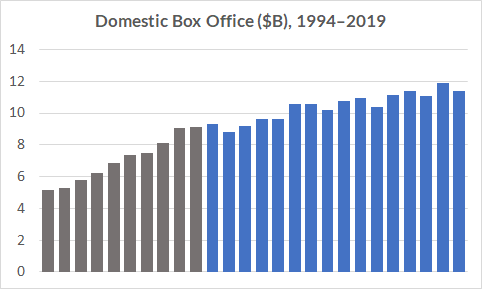

The trick was to go back far enough to show a little growth, but not far enough to show too much deceleration:

The next step was to stress that even a flat box office trend would be impressive. For example, this is AMC CEO Adam Aron in 2018:

In earlier times, the experts absolutely knew that television was going to put the movie theaters out of business, the VCR was going to put the movie theaters out of business, streaming was going to put the movie theaters out of business. And yet here we are with yet another record quarter on the books…

Part three is about taking share in that environment with consolidation, digital projection, larger screens, reclining seats, and so on — driving premium pricing and forcing smaller competitors to shut down. It’s a fairly standard template for a mature or shrinking sector. But this is far from a standard business.

1. The Right Story

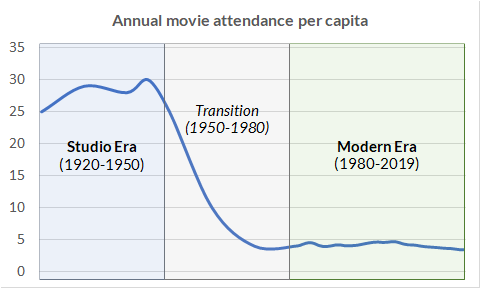

Let’s start with a better metric, and a longer time frame:

The older data is fuzzy and I had to make some rough estimates, but you get the point: whoever these “experts” were that said TV would kill movie theaters, they were absolutely right. And if VCRs and other improvements on TV have not had the same dramatic effect, maybe there just wasn’t much left to kill.

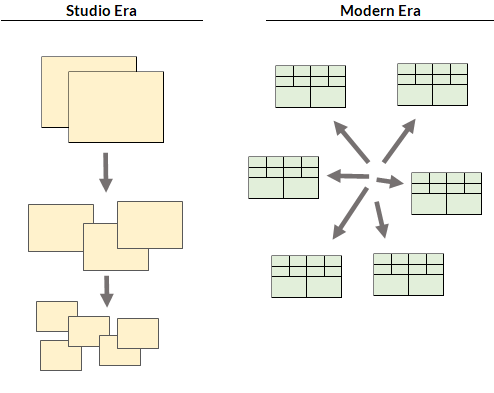

But that’s not the right story either. We’re talking about two different business models, with very different real estate:

In the studio era, movies had a first run in very large downtown theaters (“picture palaces”) which were often owned by the studios. Then they were pulled from the market (“cleared”) before a second run at smaller and cheaper theaters, and so on. During the transition years, this system collapsed and was eventually replaced by the modern system of multiplexes and “saturation booking,” with most films opening everywhere at once.

Why did the multiplex format take over? There were multiple reasons, but you can see how they work better for this blockbuster system of wide releases and big opening weekends. By staggering the showtimes every half hour across multiple smaller auditoriums, you can accommodate a larger total audience and run more of them by the same concession stand.

At the same time, studios were beginning to make more of their money from licensing their catalog for broadcast, spinoffs, VHS and DVD sales, pay per view… in other words, from television. This long tail reinforced the promotional value of big openings, which in turn demanded huge ad budgets that were largely directed back to TV. And given all that, it’s not surprising that most of the M&A activity during the modern era was bringing the studios under the umbrella of TV networks.

So let’s try it again from the top. Hollywood was built by theater moguls, but those theaters are long gone. And like their audience, the studios have pivoted towards television, which in turn has supported a new set of theaters. We’ve gone from a system where movies were made to fill theaters to one where movies are made to be watched mostly at home, and theaters are built to promote them.

If this sounds cynical, remember that we’re talking about the business models, not the content. Both systems produced plenty of great movies, and if anything those “transition” decades were a creative peak. So if you’re thinking about this as a movie fan, another transition might be exactly what you want.

But it would not be a fun time to own theaters. And even before COVID, we were running out the clock on the modern era.

3. The Beginning of the End

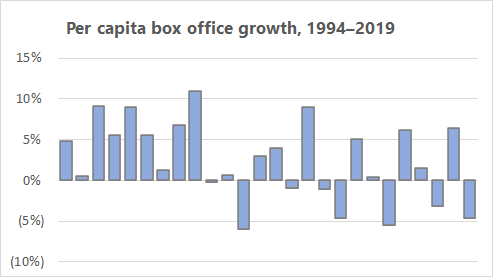

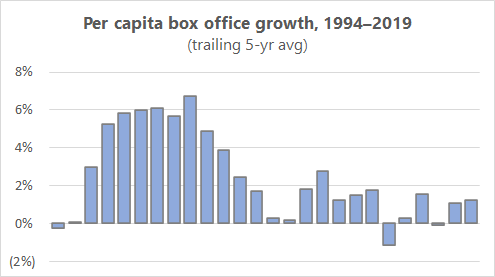

How do we know that we were approaching another transition? Let’s revisit that 25-year box office trend from the first section. We can start by stripping out population growth…

…and using a moving average to smooth out the noise from each year’s particular film slate:

Now it’s getting easier to see a pattern — especially if you recall the multiplex overbuilding wave that peaked in the late ’90s, leading to widespread bankruptcies and restructuring. Maybe some of that new supply really did claw back some incremental demand from TV and other alternatives, between the added peak capacity and new features like stadium seating. But those were one-time benefits, and we quickly returned to a softer long-term trend.

And to the extent the major chains have been able to do a little better by taking share from independent theaters with consolidation and capital projects — well, that’s coming back to bite them now, because much of it was financed with long-term leases that are still not paid off.

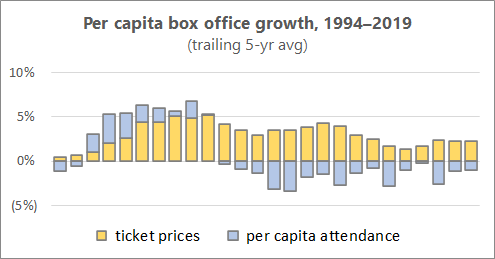

But let’s keep going and tie this all the way back to the long-term attendance trend, by breaking out the above chart into traffic and ticket:

Note that falling attendance is bad for theaters even if it’s fully offset by higher ticket prices, because (among other things) they’re selling less popcorn. But these are also not independent variables. Are ticket prices being raised to offset lower attendance, or are higher ticket prices driving attendance down?

Again, the second strategy would not appear to be in the theaters’ best interests. But from the studios’ perspective, the efficient frontier is less clear. If it’s the opening box office dollars that matter for promotional purposes, and they can only generate a certain fixed amount of opening weekend demand that is relatively inelastic (e.g. from die hard Star Wars fans) then it may make sense to simply charge more. And of course, the fewer people have seen a movie in the theaters, the more there are left to watch it at home.

Whatever’s going on, just extrapolating these trends for another ten years would be bad enough from the theater side. But were there any additional signs that we were approaching another painful transition to a new era, even before the pandemic?

Yes. One was the rise of the streaming studios, and another was the DOJ officially winding down the Paramount decrees. But I’d say the most important was actually MoviePass. Because it exposed (if only for a few months) what I just suggested above — that there is substantially more demand at lower effective pricing, and the gap between the ideal pricing strategy for theaters and studios is growing larger.

MoviePass didn’t have a way to profit from that, but they inspired (or at least accelerated) similar subscription programs from the theater chains, which were already putting them on the path to a showdown with studios. And even before last year’s wipeout, that was looking like a one-sided showdown where the studios had all the leverage.

4. What comes next?

I don’t know, but I hope I’ve convinced you that any “scenario” based on a return in X years to Y% of prior box office, with Z% of competing theaters shutting down, is missing the point. I mean, just imagine underwriting theaters that way in 1950. Even if you had been conservative enough with your attendance forecast — which is hard to imagine — you would certainly not have predicted the coming changes in theater formats and distribution models. In fact you would have been wrong about formats almost immediately with the drive-in theater boom of the ’50s, one of the first of many curveballs during those transition decades.

Actually, an even more basic problem with a box-office based forecast is that if it doesn’t fully recover in the next year or two, the industry may find a way to stop reporting it entirely, in favor of some new metric that’s easier to manipulate and promote. And maybe that’s what theater investors should want — because getting those opening box office numbers out of the headlines is the first step in reversing that tradeoff in the chart above, and using subscriptions or variable pricing tools to start lowering effective prices to recover attendance.

But it’s only the first step. What you really need for any sustainable theater comeback is a realignment of interests with the studios, which is to say a return to some elements of the old studio system.

I could argue that was already starting to happen in this franchise era, but one next step from here would be studios building up their own small theater circuits. For example, how big a step is it from a Star Wars ride at Disneyland to a few dozen Disney theaters around the country that open the next Star Wars or Marvel movie a day early for Disney+ members, and fill in with repertory Disney programming when they don’t have a new film to promote? And at this point, what could the existing theater chains really do to stop them?

5. What to do about it

Any way you slice it, this is not a good story for the theater industry, certainly not in its current form. But it also contradicts much of the conventional wisdom about the advantages of the big three US chains over smaller ones. Whatever incremental value the national chains generated in the past came largely from their role as an intermediary between landlords and studios, using scale on each side for leverage over the other. And their landlord base is still fragmented, but the studios were consolidating just as fast as theaters, and whatever leverage was left on that side has now evaporated.

What are the general lessons for underwriting other leisure businesses? I laid out a few in a 2019 piece called The Long Arc of Leisure Demand. But the most important one here is to always start with traffic rather than revenue, especially as a lender or landlord making long-term commitments. Charging more to fewer people can work for a long time, but it can’t work forever and it’s never as simple as it looks.